Texas represents a unique case among all the states in the US in dealing with COVID-19. It was among the first states to reopen in the Spring of 2020 as well as 2021. State and local governmental offices sued each other over COVID-19 control measures.

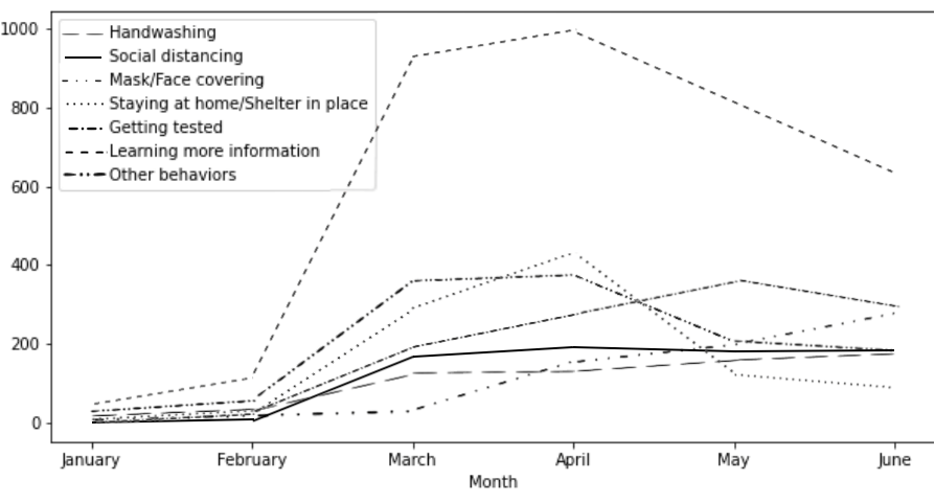

In this collaborative study involving authors from four universities in Texas (Texas A&M, University of Houston, UT Health, and Rice), we examined the Twitter message sent by all the public health agencies and emergence management organizations in Texas during the first six months of 2020. We used BERT, a natural language processing tool developed by google, to automatically classify these tweets in terms of their functions, prevention behaviors mentioned, health beliefs discussed. We also explored the relationship between tweet contents and public engagement (in term of likes and retweets).

Here are some of our findings:

• Information was the most prominent function, followed by action and community.

• Susceptibility, severity, and benefits were the most frequently covered health beliefs.

• Tweets serving the information or action functions were more likely to be retweeted, while tweets performing the action and community functions were more likely to be liked. Tweets communicating susceptibility information led to most public engagement in terms of both retweeting and liking.

Tang, L., Liu, W., Thomas, B., Tran, M., Zou, W., Zhang, X., & Zhi, D. (In press). Texas public agencies’ tweets and public engagement during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Natural language processing approach. Journal of Medical Internet Research: Public Health and Surveillance. [Preprint here]